This article on contemporary women artists photographers from Africa is part of the series on photography, which presents the history of photography, contemporary artists who are changing minds and the article on those artists who have adopted an inventive creative process.

Far from the colonial heritage and its generalizations, these women artists photographers mark an undeniable break with a photography too often reduced to the hero’s gaze. Those presented here are remarkable in that they rise above the work and exude, definitively, a particularly unique imaginary, all the more so as they devote themselves entirely to the practice.

Photographs of Africa are the narratives of the regions and are essential to the development of contemporary legends. In any case, more than that, they question governmental issues by involving photography itself. These contemporary women artists photographers inform us that they are creative bearers of memory and message.

Beyond the borders between French and English-speaking nations, this visual tour leaves us with a question: could we one day speak of African political photography?

Berni Searle

Since the 1990s, Berni Searle has been developing a body of deeply engaged work in mediums such as photography, video and performance. Her own body, which she frequently organizes, is the encapsulation of a global body wounded through different identities.

As a woman, as a mixed race, as an African, Berni Searle wants to help us remember the various wounds, visible or undetectable, that permeate South Africa’s post-politically sanctioned racial segregation.

Berni Searle belongs to the category of women artists photographers, and in her work she sometimes addresses herself, turning her gaze as if to bring out here the singular predetermination or oceanic exchange of her former neighborhood in colonial times.

At times, brutality insinuates itself all the more firmly into her works, which she depicts by covering the leaves of the body with henna before compacting them until the fabric appears as wounded. Similarly, her cheek could become the mode of a denunciation that alludes to various stories of abuse, through generally huge images: Catholic cross, windmill, English crown…, whose engraving comes to sink into her skin.

In his work, Berni Searle attempts to break away from the clichés associated with the representation of people of color: the characters are more fluid.

In the long run, water and fire have become repetitive elements in her creations, used as analogies for erasure: the crepe paper figures she breaks in water until they turn pale, or the recordings of the three-part series “Black Smoke Rising” in which she alludes to the horrific act of lynching with tires, used in South Africa in the last long periods of apartheid.

Maud Sulter

English visual artist, photographer and essayist, Maud Sulter is an artist and women’s activist of Ghanaian origin.

At the age of 17, Maud Sulter moved to Glasgow to study at the College of Fashion in London and then obtained a post-graduate degree in visual studies at the University of Derby. She began her career as a writer and published her most memorable collection in 1985, “As a Blackwoman“, which won the Vera Bell Prize. That same year, she participated as a visual artist in “The Thin Black Line“, her major exhibition.

Another milestone in her career was the landmark publication of a book she initiated with artist photographer Ingrid Pollard in the 1980s.

Around 1999-2000, Maud Sulter opened a gallery, Rich Women of Zurich, in London’s Clerkenwell district, to showcase her work and that of local artists. Since the mid-1980s, her creations have tested the codes of Western art, to rebuke the segregation and invisibilization of Africans.

Maud Sulter strives to put people of color at the center of an art history that prohibits them. In her works, she uses different mediums.

In 1987, “Sphinx,” her most memorable independent exhibition, featured a series of high-contrast photographs taken on an island off the coast of Gambia, where slaves deported to the Americas were arrested.

In 1989, “Zabat,” a series of Cibachrome representations, featured her and nearly eight other artists, each embodying a dream of old Greece. Her visual practice is exceptionally effective and has earned her several awards, including the British Telecom New Contemporaries Award and the Momart Fellowship from the Tate.

Maud Sulter was for a time the head of the MFA program at Manchester Metropolitan College and researched the cultural history of the African diaspora in Europe, which led her to deliver a few series driven by the existence of black women’s lives.

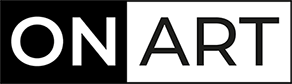

Her series “Hysteria” features Edmonia Lewis, a sculptor of African American and Native American descent, who made her career in Rome. Some of Maud Sulter’s work centers on Jeanne Duval, the friend of writer Charles Baudelaire. Her most popular work, “Syrcas,” deals with the overseas slave trade and the oppression of minorities of African descent in the extreme Europe of the 1930s and 1940s through photomontages.

Her project, “Sekhmet” in 2005, revisits her set of experiences in which she takes up the visual chronicles of her two families, Scottish and Ghanaian, and accompanies them with sonnets summoning the real factors of the diaspora.

Taken by cancer at 47, Maud Sulter’s work is still extremely significant today and was the subject of a retrospective in 2015 through the exhibition “Maud Sulter: Passion, at Street Level Photoworks” in Glasgow, her hometown.

Lalla Essaydi

Lalla Essaydi‘s specialty as a Moroccan painter, photographer and visual artist is to explore the intersection of the female condition with issues of proximity, history, culture and politics. An obvious supporter of the category of women artists photographers, her work, deeply influenced by her transnational life, focuses on the restrictions of physical, social and mental space for women in the Muslim group.

Lalla Essaydi was conceived not far from Marrakech in a Muslim family and moved to Saudi Arabia. Her imaginative career began when she focused on painting as an adult at the École des Beaux-arts in Paris in the mid-1990s. She was both fascinated and overwhelmed by the nineteenth-century Orientalist art she found in museums.

Lalla Essaydi then moved to the United States and enrolled at Tufts University in Medford before graduating from the Boston School of the Arts in 2003 with a degree in fine arts. It is from this moment that photography became a central vehicle of articulation in her practice.

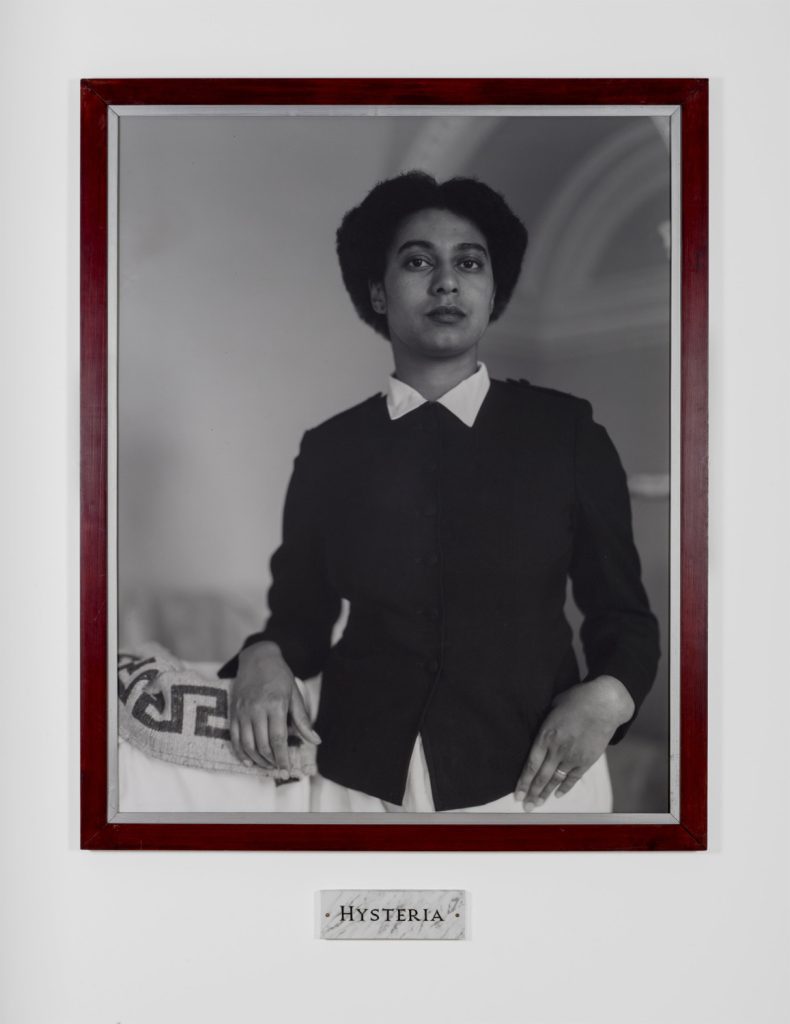

© Lalla Essaydi, Courtesy the artist and Edwynn Houk Gallery, New York

Lalla Essaydi recaptures the Morocco of her youth, both geographically and reflectively, in her large-scale, tediously created works that dismantle the generalizations of Orientalism: the mantle, the odalisque, and the group of concubines. Through her work, she believes that the viewer must understand that Orientalism is a voyeuristic custom and is instead in search of the excellence of the lifestyle addressed.

In 2010, the Louvre Museum acquired her photograph “La Grande Odalisque” made in 2008 and exhibited it in dialogue with Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres’ version.

Lalla Essaydi is best known for her series of photographs in which she relates writing, the hidden female body and the cozy entrails. She takes Moroccan women, usually family members or companions, as models and uses henna to etch elements of Arabic calligraphy onto their bodies, clothing, or stylistic themes, thus blending two usually gendered visual dialects into a virtually obscured living text.

The way she traverses space, whether structural or figurative, private or public, is an essential component of the way she studies orientation.

Lalla Essaydi goes beyond the limits of the intimate to deal with subjects, arranging in the dazzling collections of the mistresses of the royal residence Dar al-Basha of Pasha Thami el-Glaoui. In one of her series, “Bullets,” she uses projectile casings to shape brilliant mosaics around her models, and squeezes in a more expansive structure and expressive wildness.

In each of her photographs, she shows women defying the crowd with their certainty and control of space.

“Revisions,” the significant retrospective of Lalla Essaydi’s work, was held at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African Art in Washington, D.C., in 2012-2013, and highlighted a range of mediums. She was also featured in the independent exhibition at the San Diego Museum of Art and the Newport Art Museum.

Fatma Charfi

Tunisian visual artist and performer, student of the School of Visual Arts of Tunis, Fatma Charfi is the main woman accepted in her audiovisual class.

She continued her studies at the Sorbonne and obtained a doctorate in art sciences.

In the latter part of the 1980s, Fatma Charfi moved to Bern. Exile became a central subject in her work. In 1990, she made a small person of 7.6 centimeters long, made of tissue paper that she dipped in black ink, then dried, cut and rolled, following the usual procedure of making bread, used by Tunisian women.

Fatma Charfi duplicates this person and scatters it throughout her creations as if to review the challenges of exile and the accumulation of feelings. In 2004, in Dakar, she organized her exhibition “Peace Laboratory Project: the Offering“.

A pinnacle of 2.3 meters, vertical installation, made of Plexiglas boxes that contains countless figures that seem to be suffocating. On the ground, different figures are scattered on a rectangular frieze fixed with retentive cotton and covered in places with a net, so that the characters seem sometimes saved, sometimes held.

Each figure is, by its reiteration, dehumanized. However, to the redundancy are added unpretentious contrasts: not only in the dolls’ state of mind and in their game plan, but for each of them by the way it has been inflated, twisted or wrinkled.

The overall impact, which eliminates the uniqueness of the figures, furthermore envisages a large number of implications to be seen.

Zanele Muholi

One of her women artists photographers, Zanelu Muholi is originally from South Africa and an extremist who lived her childhood in a municipality on the outskirts of Durban, Zanele Muholi moved to Johannesburg.

Following a two-year course in the studio of photographer David Goldblatt, she defined the standards of her methodology, which she characterized as directly related to the group of LGBTI people in South Africa, who, although allowed, continue to suffer from malice, segregation and disparity.

In 2006, she initiated a project to name individuals and the different periods of their personal development. Significant to her methodology, this ever-evolving series consists of approximately 300 photographs of women, met across the country, with whom she establishes a relationship for shared understanding.

Taken at different times in their lives, these models are unmistakably photographed to a similar standard, in bust, front or three-quarter view, sketched at equal distance, indoors or outdoors, clearly, without ploy, style or ensemble.

Zanele Muholi gives visibility to black South African lesbian women, reveals their presence and offers them the possibility to assert themselves.

Beyond the story, these images, of an obvious authenticity, impose themselves in a face-to-face of an uncommon power.

Wearing a crazy look, sporting haircuts, outfits and embellishments as different as they are fluctuating, Zanele Muholi willingly shows herself in moderate settings, to play devilishly with the generalizations linked to African femininity.

Executed with clarity, these photographs pay particular attention to the pigmentation of the dark body.

Considered today as an important figure in contemporary photography, both in terms of activism and art, where she embodies the first political second of art after the end of segregation, Zanele Muholi is today at the head of a new generation of contemporary women for whom she has undoubtedly prepared the way.